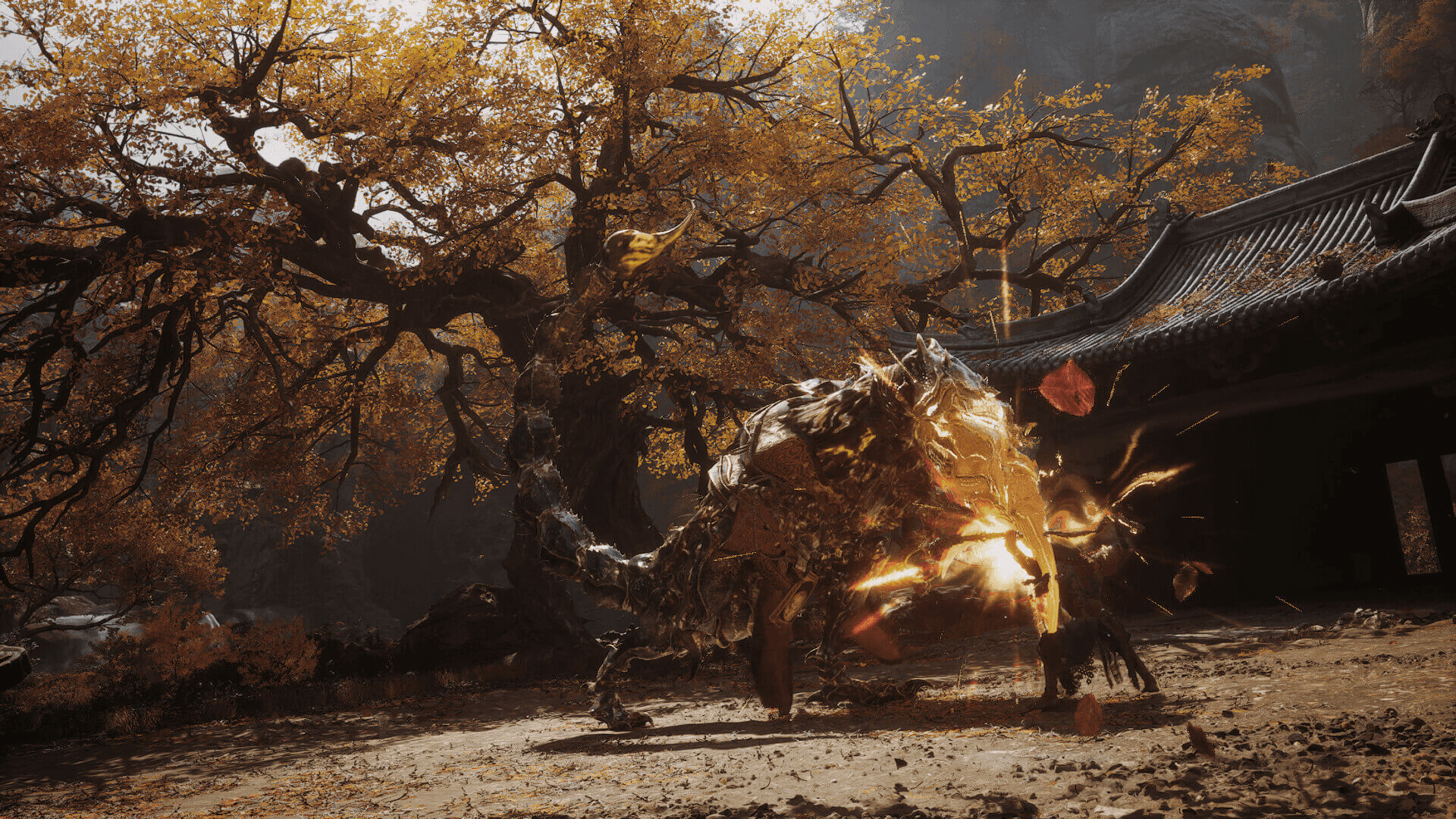

August 20, 2024. A date that, for most, was marked as the release of the much-anticipated game Black Myth: Wukong. But for those who knew the tales, this day held a deeper, almost mystical significance. It was the birthday of the one and only Monkey King, The Great sage, Heaven’s Equal, a figure of legend, worshipped as a god for centuries.

We’re about to dive into a wild journey that blurs the lines between mythology and reality, where the mighty Sun Wukong isn’t just a character in a book—he’s got temples, followers, and a legacy that stretches across China and beyond. Ready to explore the origins of this legendary figure and uncover the secrets of his enduring worship?

The Origins of the Great Sage Worship

Okay, so here’s the deal: It might sound a bit unconventional to consider Sun Wukong as a deity worthy of worship.However, the belief in the Great Sage is a deeply rooted and widespread folk tradition, with a global influence that dates back centuries. This isn’t just some small-time belief—it’s a deeply rooted tradition that’s spread all over, especially in China. The story of Sun Wukong isn’t just limited to Journey to the West—it’s a belief system that’s shaped and been shaped by this legendary novel.

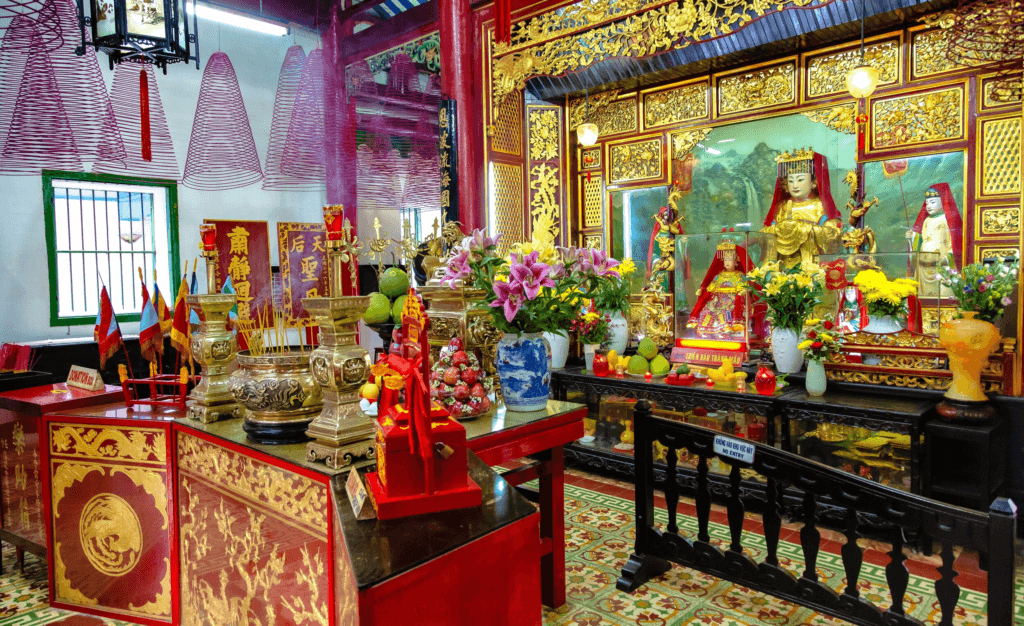

Statue of the Great Sage Heaven’s Equal, Take note of the Qitian Dongfu Ancestor Temple in Pingshan, Fuzhou, China.

In places like Fujian, Zhejiang, and Guangdong in China, you’ll find shrines and temples dedicated to the Great Sage everywhere. Among these regions, Fujian stands out as the epicenter of this belief, boasting over 38 major temples marked on maps, not to mention the numerous smaller shrines scattered across villages and countryside. So, what makes the belief in the Great Sage so deeply ingrained in Fujian’s culture? And how did the artistic image of Sun Wukong from Journey to the West find its way into real-life worship?

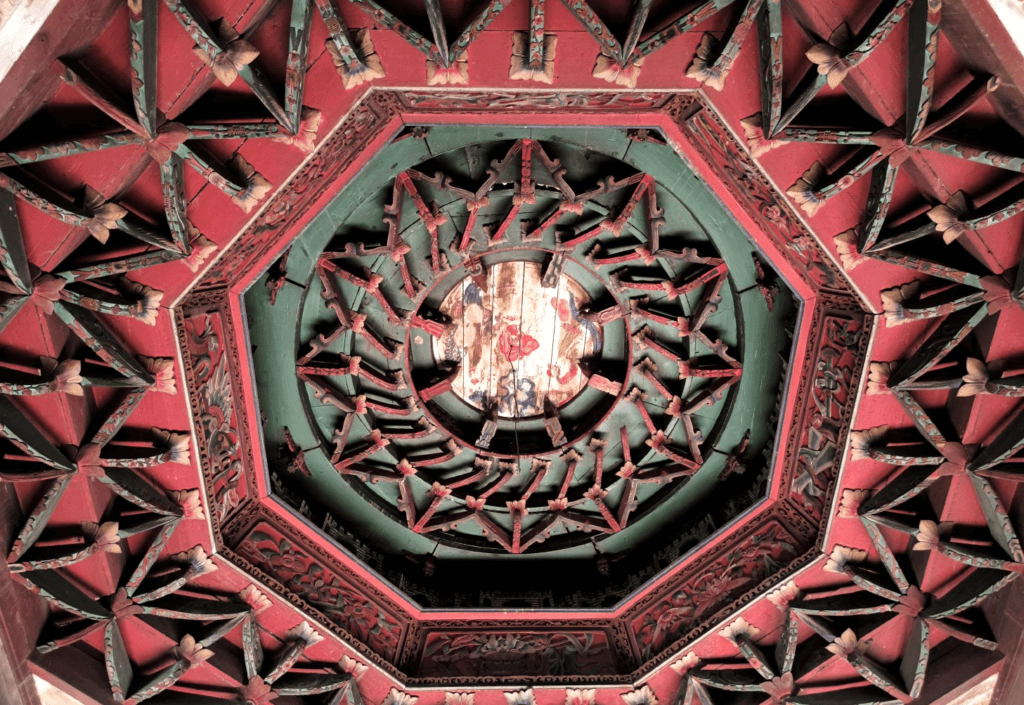

Photo of the Great Sage Equal to Heaven Temple in Guangze County, Fujian Province, with the inscription “Great Sage’s Benevolent Voyage” on the plaque.

Journey to the West: Where Myth Meets Faith

“Long ago…our ancestors worshipped the monkey gods out of fear. They were the protectors and the punishers, and we, mere mortals, could only offer our prayers and sacrifices. But as time passed, our fear turned to respect, and respect became devotion.”

Now, let’s rewind a bit. Fujian was a land of mountains and mystery, where the wind carried stories as old as time, and back in the day, the locals had more than their fair share of run-ins with monkeys—some of which didn’t end too well. These folks had a strong belief in spirits and gods, and monkey worship in Fujian goes way back, way before Journey to the West became a hit. Originally, people worshipped these monkey gods out of fear—yep, they were scared of what these mischievous creatures could do. They’d offer sacrifices to keep these “evil gods” at bay. It’s kind of like how ancient people everywhere worshipped deities to avoid disaster.

But as time passed, this monkey god worship evolved. What started as a fearful veneration turned into something more complex, influenced by Buddhism, Daoism, and local traditions. And boom—the Great Sage cult was born, with Sun Wukong as the star. This belief really took off in eastern and northern Fujian, where hundreds of temples still stand today. This shows that the image of folk deities isn’t set in stone; instead, it evolves with the times and shifts in societal attitudes.

In Fujian, each deity has a specific role, and every shrine is dedicated to certain prayers. Folks pick their shrine based on what they need—health, wealth, protection, you name it. When they enter a temple, they burn incense at the entrance before moving to the main shrine to make their requests. This blend of Buddhist and Daoist practices, mixed with local customs, has shaped how people see and interact with their faith.

The Evolution of the Great Sage: From Myth to Local Hero

The story of the Great Sage didn’t just come out of nowhere; it was woven from the threads of ancient beliefs, evolving over time into a symbol of strength and protection. It evolved from a long tradition of monkey worship that dates back to the Qin and Han dynasties. With the introduction of the Hindu monkey god Hanuman through maritime trade and the rising popularity of Journey to the West, the image of Sun Wukong as the Great Sage was solidified. This image was not just a literary creation; it was deeply intertwined with local beliefs, transforming the “evil monkey” into a revered protector and hero.

The reverence for Sun Wukong is echoed in the famous line from Mao Zedong’s poetry: “Today we cheer the Great Sage, for the evil mist returns again.” This sentiment reflects the people’s deep connection to a deity who symbolizes courage, justice, and the power to ward off evil—qualities that resonated strongly in a region frequently plagued by natural disasters. For the people who came to worship, he was more than just a deity; he was their protector, their hero.

The Great Sage’s Lesser-Known Brother: A Tale of Two Deities

While Journey to the West has firmly established Sun Wukong as the Great Sage in popular culture, there is an intriguing twist in the narrative. In certain regions of Fujian, the Great Sage is accompanied by a brother known as Tongtian Dasheng, or the “Heavenly Sage.” According to some scholars, it was Tongtian Dasheng, not Sun Wukong, who originally protected Tang Sanzang on his journey to the West.

IIn 2004, a “tomb of the Monkey King and his brother” was discovered on the main peak of Baoshan in Shunchang County, Nanping, Fujian.

In places like Shunchang, which today prides itself as the “ancestral land of the Great Sage,” the belief in Tongtian Dasheng was once more prevalent than that in Sun Wukong. Over time, as Journey to the West became more popular, the worship of Tongtian Dasheng diminished, but it never completely disappeared. Even today, in local processions, the Great Sage is sometimes referred to as “Tongtian Ye,” showing how these overlapping identities continue to coexist in folk belief.

Global Reach: The Great Sage Goes Worldwide

Chinese wasn’t the only one who worshipped the Great Sage. Besides the various regions of Fujian China, countless others shared their devotions. They weren’t just praying to a character from a book; they were connecting with a deity whose roots ran deep through the soil of their history.

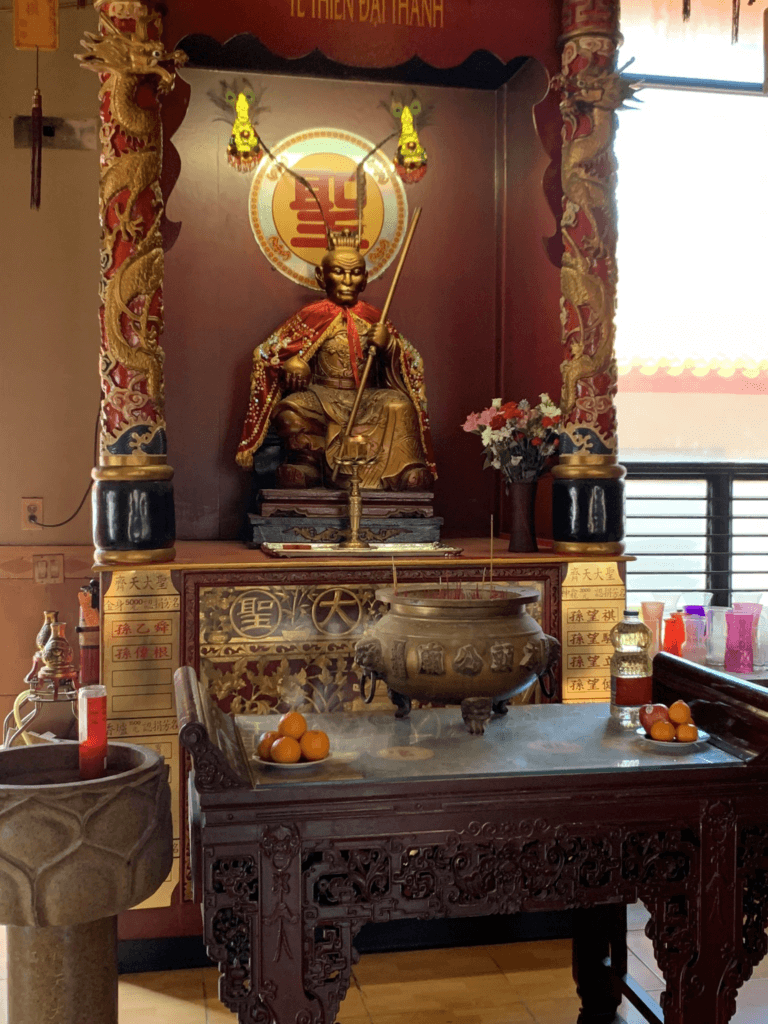

With Fujianese people moving around and spreading their culture, the belief in the Great Sage has gone global. Temples dedicated to Sun Wukong can be found all over—from Taiwan and Hong Kong to Singapore, and even as far as the United States. For example, there’s a Teo Chew Vietnamese Buddhist Temple in Houston, Texas, with an altar just for the Monkey King. And in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Sun Wukong was a big deal among Chinese immigrants, especially those involved in the Chee Kong Tong, a secret society with roots in anti-Qing rebellion.

The Monkey King altar of the Teo Chew Temple of Houston, Texas, USA. Take note of the Vietnamese words at the top. Image found on Twitter.

Sun Wukong’s rebellious spirit, as seen in Journey to the West, really resonated with these communities. They saw him as a symbol of defiance and resistance against oppressive forces—pretty cool, right?

A photomanipulation of Sun Wukong above the title logo from the American Gods television show. The program is based on the 2001 novel of the same name.

As we continue to celebrate the legacy of the Monkey King in both ancient traditions and modern pop culture, the upcoming release of ‘Black Myth: Wukong’ serves as a testament to the enduring power of this legendary figure. Whether in temples or video games, the Great Sage continues to inspire and protect, bridging the gap between past and present. It was a connection to something far greater, something that had spanned lifetimes and crossed the boundaries of myth and reality.

Sun Wukong’s story continued to be rewritten and retold, listeners could feel the weight of centuries upon them. They weren’t just hearing a tale; they were becoming part of a legacy, a living thread that connected them to their ancestors and to the Great Sage.

Source:

Risse, G. B. (2012). Plague, fear, and politics in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cassel, S. L. (2002). The Chinese in America: A history from Gold Mountain to the new millennium. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Journey to the West Research: The Worship of Sun Wukong in 19th-century America